Teaching and Learning

Page Navigation

Frameworks

-

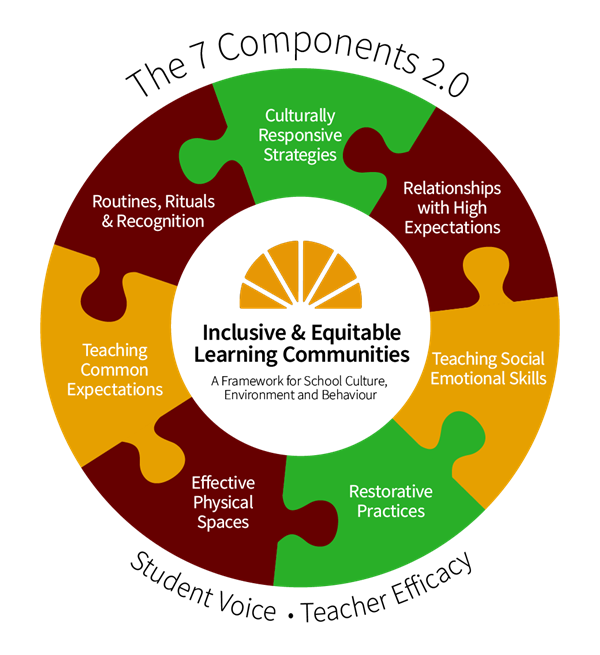

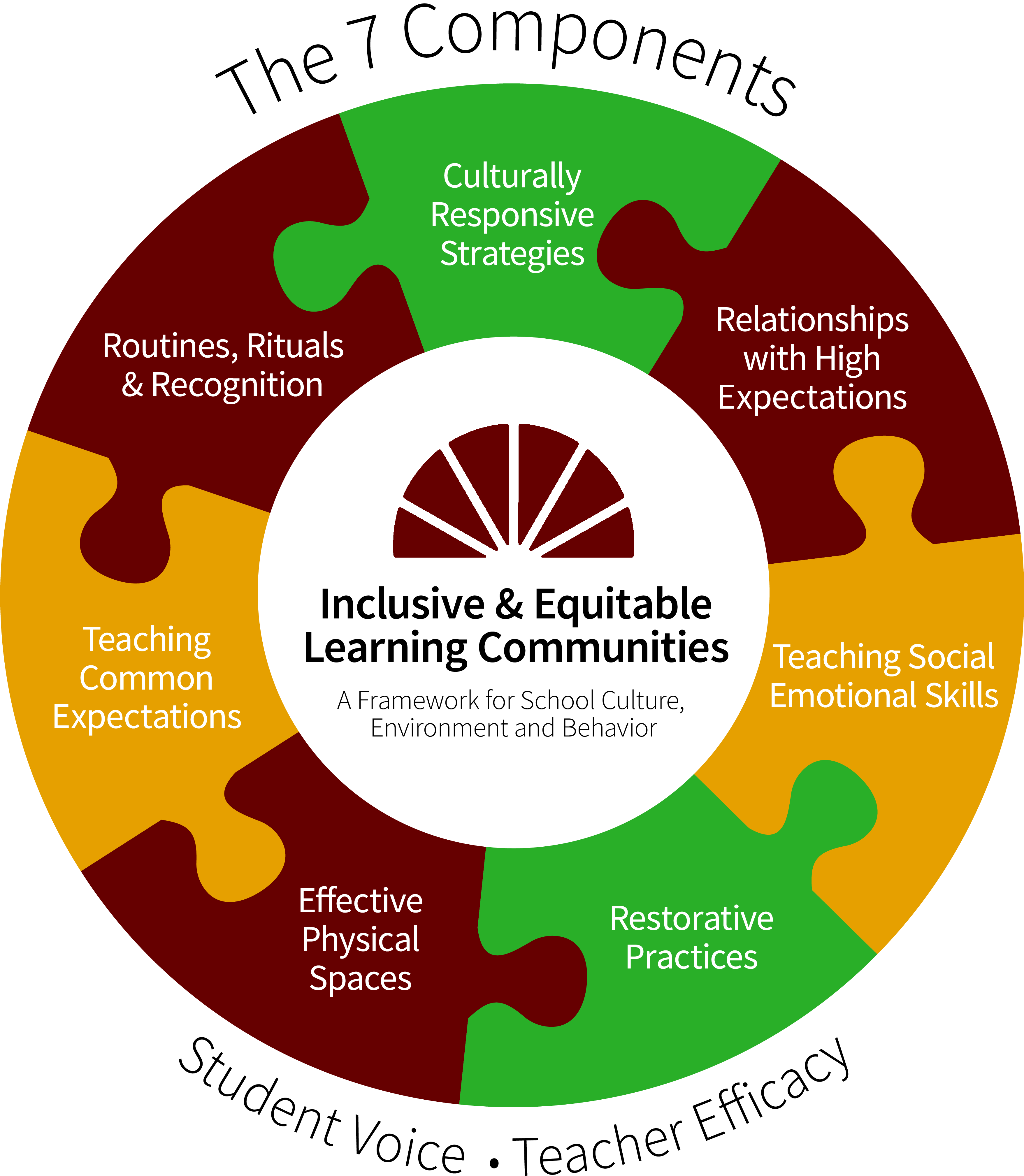

The West Linn-Wilsonville School District uses several frameworks for student instruction, including the five dimensions of teaching and learning and the seven components of inclusive and equitable classrooms.

Inclusive Schools

-

Guiding Principles

In the West Linn-Wilsonville School District, we believe that all students belong.

The evidence from 30 years of educational research shows that all students do better in inclusive settings - including students with and without disabilities.

We are committed to creating equity and inclusivity throughout our learning communities.

Promoting inclusive and equitable classrooms involves 7 key components:

- Effective Physical Spaces

- Teaching Common Expectations

- Engagement Strategies

- Teaching Social-Emotional Skills

- Relationships with High Expectations

- Routines, Rituals and Recognition

- Restorative Practices

Resources

Positive School Communities and Restorative Practices

7 Components | Vision and Guiding Questions

Restorative Practices

-

Guiding Principles

“How do we create learning communities for the greatest thinkers and most thoughtful people for the world?” is the mission question of the West Linn-Wilsonville School District. We believe in the necessity of building and sustaining positive and safe school communities to promote the social, emotional, physical and academic health of all community members. Students learn best when they experience strong, healthy relationships with peers and adults.

The following guiding principles influence district practices for establishing and maintaining positive school communities:

- Everyone deserves to feel valued, safe, cared for and a sense of belonging to their school community. All members have something positive to contribute to their school community.

- We are committed to achieving equity and inclusivity throughout our learning communities. Each learner deserves the opportunity to succeed. Culture and diversity are assets for our communities that are to be respected for their multiple perspectives on learning, definitions of success, and pathways for self-determination.

- All community members will be supported to feel safe and express their true identities.

- Schools teach and facilitate informal and formal processes to proactively build relationships and a strong sense of community (see the “all” section below).

- Schools make explicit behavioral norms for communication and conduct within the school community. Students are accountable for these norms and for demonstrating effort toward learning.

- Within the school environment, establishing a sense of collaboration rests on genuine respect for the participation of young people in promoting a strong, healthy and safe school community. Children respect adults who, in turn, respect young people’s ability to exercise meaningful choices.

- Students are supported in the learning process to be positive members of their school community and can be trusted to solve their problems. All children experience lessons on how to safely and peacefully resolve conflict. They are expected to listen and take restorative action when harm is caused.

- Schools promote accountability and responsibility through personal reflection within a collaborative environment. With practice, young people improve skills for careful listening, empathy, perspective-taking and responding to the needs of others.

- Adults model that we make mistakes and have an opportunity to make things right.

- Students are taught to understand and regulate their emotional state, which helps them form stronger relationships and avoid choices that are hurtful to others or the larger school community.

- Harmful actions impact the whole school community. When harm is caused, we address the harm and repair relationships.

Procedural Guidelines and Practices

The West-Linn Wilsonville School District implements a comprehensive range of evidenced-based practices to build and sustain positive and safe school communities. We define seven components in our overall framework for Inclusive and Equitable School Communities: teaching common expectations, teaching social-emotional skills, restorative practices, establishing routine/rituals/recognition, engagement strategies, relationships with high expectations and effective physical spaces. Click on the image to the right to learn more about each of the seven components.

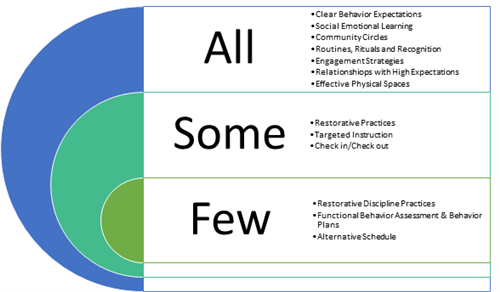

We are strategic in the way we implement the components of our framework for school culture, environment and behavior. Our district uses an “All-Some-Few Model” to differentiate the needed supports for children. We begin by planning for and facilitating components that will positively and proactively serve all children. Differentiated support and problem solving is then provided as needed for small groups and a few individual students.

All

Schools employ a wide range of proactive practices and strategies for all students to experience and participate in building a strong school community.

- All students participate in school-wide and classroom-based social and emotional learning (SEL) opportunities. The purpose of SEL is to develop skills to understand and regulate one’s emotional state for personal health and strong, safe relationships. We teach lessons from the Second Steps SEL curriculum across all primary schools.

- Schools explicitly define, teach and review behavioral expectations.

- Whole school assemblies promote positive behavior and teach skills for maintaining healthy relationships. For example, a school may hold an assembly to announce “kindness” as the character focus of the month. Children will be encouraged to demonstrate extra amounts of kindness and notice kind actions by peers. Children describe actions of kindness they notice on a paper leaf and glue the leaf to a large paper tree centrally located in the school.

- Morning Meetings and Community Circles occur regularly in classrooms to teach skills such as empathy, kindness, and careful listening. Circles are designed to create a safe space for all voices and to encourage each participant to step in the direction of their best self.

- School counselors and teachers facilitate lessons in classrooms about personal safety, problem-solving and ways to prevent bullying.

Some

Some students need more care and support in order to feel connected to the school community. Additionally, when harm is caused, students need extra care and support to repair the harm. Restorative practices are used when harm has been done to another person or the school community, in order to restore relationships and promote positive choices in the future.

Restorative practices are not a component of a singular program or process, rather a philosophy and practice based on creating a culture of relationships, building safe school climates, developing social and emotional skills, creating time to build community and make things right, and being inclusive teachers and focused learners.

What it is...

What it isn’t...

A philosophy and set of practices to guide the way we believe and act in all of our dealings with one another (leaders, staff, students); seeing every instance of wrongdoing and conflict as an opportunity for learning.

A set of prompts or actions to simply address behavior without critically reflecting on the actions of those involved, the circumstances, or how systems or structures may perpetuate conflict and exclusion

Positions of authority working WITH the wrongdoer, aiming at restoring the student into the community.

Positions of authority enacting discipline TO the wrongdoer, aiming at only excluding the student from the community.

May still include school discipline.

A substitute for school discipline

Application of a continuum of informal to formal practices used systemically, not situationally: leadership to staff, staff to staff, staff to students and students to students.

A “quick fix” or occasional intervention applied only to a few students.

Involves a fair process for everyone (engagement, explanation, expectation clarity)

One party feeling unheard, profiled, biased towards or experiencing an unfair, uneven playing field.

The West Linn-Wilsonville School District draws from a range of restorative practices, depending on the needs of students and the larger school community. A few of the more common practices are described below, but the list is not exhaustive.- Restorative Circles help build relationships and community. As an example, the “Showing Gratitude and Appreciation Circle” is used to build relationships through positive recognition, increase skills in giving compliments and increase awareness of the strengths of each child. Restorative Circles also provide a structure and process for addressing conflict and harm. The “Being Left Out Circle” is implemented to learn about social exclusion and develop practices to prevent negative social dynamics. A Restorative Circle might involve an entire classroom or a small group of students and/or adults.

- Restorative Dialogue involves a meeting between the person who harmed others, the people directly impacted and a trained facilitator (teacher, counselor, principal, etc.). All participants recount what happened to them at the time of the incident to gain a clear understanding of the full impact of harm. They then collectively decide what to do to repair affected relationships and prevent further problems. Agreements are recorded and followed-up on.

- A “social story” may be co-created with a student. Social Stories are a social learning tool that supports the safe and meaningful exchange of information between parents, professionals, and students. Authors follow a defined process that begins with gathering information, discovering a topic that ‘fits’ the audience, and the development of personalized text and illustration to teach new social learning.

- In Restorative Mediation, a neutral party (which could include a peer) helps disputing parties identify the problem and arrive at a mutually agreeable approach to resolving the dispute.

- Targeted instruction, behavior support plans and/or extra supervision are implemented as needed to ensure safe and healthy behaviors are learned and practiced by students.

- Check in/check out protocols serve a variety of learning and accountability purposes. For example, a teacher may check in with a student at the beginning of the day to encourage strategies for making new friendships and then check out at the end of the day to see how the strategies worked. A staff member may also check in with a student at the beginning of each recess to review safe choices for recess games. A check out would occur at the end of recess with the student and recess teacher to see how well the safe practices were followed and how successful the student felt.

Few

A very small number of students, or few, may need more progressive levels of support. Patterns of negative behavior are sometimes the result of a complex array of factors. We work closely with children and families to understand the full context of the child’s experience and identify the most effective strategies to support them. We are careful to note the difference between making a bad choice and being a bad person. We know all children want to do their best and will do well if they can.

- We always maintain a primary focus on learning new skills to replace negative behaviors.

- We use a restorative approach to discipline. Collaborative meetings between school staff, students and families are sometimes required to solve problems. Disciplinary consequences for actions may result, and, when appropriate, the consequences are linked to repairing harm/relationships and learning new skills to solve similar problems in the future. For example, a certain class or school activities may be limited for a student while they practice new skills necessary to participate appropriately. We also strive to include students' voices in developing appropriate consequences. Students of all ages are very capable of developing plans to repair harm. They are especially invested in creating these plans when they feel listened to and understood by the adults supporting them.

- When negative behaviors persist, school teams may conduct a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA). An FBA is a comprehensive and individualized strategy to identify the purpose or function of a student’s problem behavior(s), develop and implement a plan to modify variables that maintain the problem behavior, and teach appropriate replacement behaviors using positive interventions. FBAs result in evidence-based behavior intervention plans and strategies to collect data in order to monitor and revise the plan as needed.

- Suspensions occur only in a limited number of instances and are implemented as defined by Oregon law, typically when adults need time to create or revise a plan to ensure school safety.

- Students are welcomed back into the school by adults and other students after restoring relationships with peers and/or the community. An example of a commonly practiced welcome involves the student meeting with school leadership, teacher, and family before the school day begins to emphasize learning new skills, restoring relationships, repairing harm, and moving forward.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does our district use restorative practices instead of “zero tolerance” practices?

- While it is clear that protecting the safety of students and staff is one of our most important responsibilities, evidence suggests zero-tolerance policies actually may have an adverse effect on student academic and behavioral outcomes. Psychological research demonstrates suspensions and expulsions are likely to further reinforce negative behavior by denying students opportunities for positive socialization in school and damaging the trust of adults. Additionally, research consistently indicates disproportionate percentages of African American, Latino, disabled, and economically disadvantaged students are suspended and expelled in schools with zero tolerance policies.

- While we do not subscribe to a traditional zero-tolerance philosophy, we always intervene when we learn of unsafe or hurtful behavior. We promote evidence-based practices most likely to promote positive student and staff behaviors.

- Research shows it is effective to provide clear expectations for behavior, teach skills needed to succeed in the school environment, and respond to problems with strategies to strengthen connections and relationships, rather than push students away. Schools seeking to create positive communities and respond in effective ways when problems arise are increasingly turning to restorative practices. The aim of restorative practices is to develop community and to manage conflict and tensions by building relationships and repairing harm. Restorative practices strengthen students’ connections to both staff and other students, and that’s why restorative practices support both prevention and response. Focusing on positive connections and support contributes to a positive school climate. Repairing harm and restoring relationships after transgressions help keep students connected to a positive school community.

- Clear expectations, fair and natural consequences, and restorative conversations and agreements only work when students have self-regulation, emotional knowledge, and social skills — competencies taught through social-emotional learning (SEL). Social-emotional competencies play a role in and support children for the intellectual and interpersonal demands or complexities of the formal school environment. Restorative practices that build a positive school climate and healthy relationships depend on the foundation provided by SEL: students’ abilities to take others' perspectives, be aware of their own thoughts and feelings, communicate effectively, and solve problems.

How are restorative practices implemented when children are referred to the school office or another staff member?

- Staff members may refer a student to meet with the principal, counselor, instructional coordinator, special education teacher, etc. for a variety of reasons. School leaders work with staff to clarify expectations for when problems are solved in the classroom (or playground, gym, etc.) and when children should be referred to the office or another staff member.

- Maintaining emotional and physical safety for all children is a priority as we work with the child. We also focus on understanding what happened, the impact of precipitating events and strategies for making things right. When necessary, consequences for actions are included as part of response plans.

- The principles of “Regulate, Relate, Reason” inform our work with a child referred for support.

- What happened?

- What were you thinking of at the time?

- What have you thought about since?

- Who has been affected by what you have done?

- In what way have they been affected?

- What do you think you need to do to make things right?

- Regulate: We know from brain research that when people are experiencing significant stress, anxiety, or escalation, they are physically unable to engage the thinking part of their brain at that moment. Best practice tells us that we must first support that student to regulate their sensory experience and emotions. As adults, we often do this by walking away if we are very upset, or taking very deep breaths. Children may need support in finding a way to regulate their physical response to an upsetting situation. They may need time alone to cool down, to go for a walk in the hall with an adult, or they may need something more specialized. We know that time spent in a relationship with a caring adult is the most successful regulating intervention we can provide.

- Relate: After a child has regulated, it is critical to relate. Many children who have displayed escalated behavior, may feel significant feelings of shame after their emotions have calmed down. Make a relational connection; this may involve nurturing language, or reflecting feelings, such as “I can see you’re really struggling, I’m here for you.”

- Reason: Now we can effectively move into the reason phase, where questions such as these, can help a child be accountable for what happened.

- Sometimes, consequences are necessary. Whenever possible, consequences are natural components of plans to make things right with other members of the community. For example, a child who was unsafe at recess may need to spend a few recesses in the office to create a safety plan and write apology letters to peers. Consequences are influenced by the age of the child and actions that led to the referral. Components of response plans and the severity of consequences increase if negative behavior continues and/or students do not follow through with restorative actions. Consequences may also serve as a message to community members that some behaviors are harmful and not acceptable in our schools.

What factors are considered by school staff when responding to negative student behavior?

- Every situation involving students is unique. However, there are six key factors we consider when responding to student behavior:

- Communication: Are there individual students or families who should be contacted? Did the situation impact the community at large? Is a community message possible without identifying specific students?

- Restorative Practices: Does a restorative process need to happen with any specific students? How are any students who were harmed allowed to choose their level of involvement? Is there restoration that needs to happen with the community at large?

- Discipline Process: Are there any required discipline processes for this situation? How might natural or specified consequences support the student’s learning of the needs of the community? Is there a significant safety reason that the team needs time to consider and develop a plan to address?

- Teaching Skills: Are there new skills that the student(s) need to learn? How will these be taught?

- Special Education: If the student is eligible for special education, should the IEP team meet to consider next steps? Are the current services aligned to the needs of the student? Is a behavior plan needed? If a behavior plan is in place, do we need to revise it based on new information? Do we need to consider placement options?

- Threat Assessment: Does the situation involve a possible significant threat of harm, involving severe or lethal threats of violence?

How do we communicate with families when behavior problems occur at school?

- The West Linn-Wilsonville School District understands the importance of clear, timely communication with families when children are involved in behavior problems at school. Collaborating with parents provides valuable insights to help ensure children are appropriately supported at school. We also know conflict is to be expected as children learn skills for collaboration, making friends, solving problems, etc. Isolated, low-level issues at school may not result in home communication. When patterns of negative behavior occur, or serious conflict develops, a teacher or school leader will communicate with a parent within 24 hours. Every effort will be made to contact a parent the same day that the problem occurred. If a child is injured at school, a parent will be called as soon as possible on the day the injury occurred.

- School staff will communicate information to parents that directly relates to the experience and needs of their child. We strive for open, two-way communication with families. However, we also must adhere to policies and laws for protecting student privacy. We are not able to share information about children with adults who are not parents or guardians.

- Children may be bystanders who observe a behavior problem in the classroom, playground or other areas of the school. School staff appropriately support bystanders as needed to ensure emotional and physical safety. Staff will call home if a bystander needs a high level of support at school and/or is likely to need additional support at home.

Why is a child permitted to remain in the classroom after demonstrating disruptive behavior?

- Our goal is always to create and maintain safe classrooms with high levels of student learning. The US Department of Education warns against the over-reliance on suspensions and expulsions. The Department maintains the most effective guidelines for positive school culture and behavior are:

- Create positive climates and focus on prevention

- Develop clear, appropriate, and consistent expectations and consequences to address disruptive student behaviors.

- Ensure fairness, equity, and continuous improvement

- There are conditions where children are sometimes removed from the classroom or suspended from school. Children may be temporarily removed from school or the classroom when serious threats of harm to other students or staff exist.

- Removing children from the classroom or school is an exclusionary practice. In a forward to a report on school climate and discipline, former Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, states, “in view of the essential link between instructional time and academic achievement, schools should strive to keep students in school and engaged in learning to the greatest extent possible. Thus, schools should remove students from the classroom as a disciplinary consequence, only as a last resort and only for appropriately serious infractions.”

- There are high costs associated with exclusionary practices. Students who experience exclusionary practices are more likely to drop out and disconnect from their education for three reasons: the true root of the problem was not addressed, their learning was interrupted, or the students did not feel valued or connected to their school community. The National Education Association references a study from the Center for Promise to define negative outcomes of exclusionary practices: worse academic performance, lower levels of school engagement, a greater chance of leaving school before graduation, an increase in the likelihood of involvement with criminal justice, and higher levels of school violence and antisocial behavior. Simply put, when students do not feel connected to or valued by their schools, negative behaviors are more likely to continue or even increase.

- In recognition of how exclusionary practices disproportionately impact students of color and/or those with disabilities, the Oregon legislature defined conditions for suspension of primary school age children (kindergarten through fifth grade). Students may only be suspended for non-accidental conduct causing serious physical harm, direct threats to the health and safety of students or staff, or when suspensions are required by law. Disruptive behavior may not be the cause of a suspension.

Why does it sometimes appear that a student gets to do an activity in the office, instead of being disciplined, when they have displayed unsafe or inappropriate behavior?

- In our work with children who are referred to the office for unsafe or inappropriate behavior, our goal is to achieve understanding/agreement about what happened, make things right and learn new skills for more appropriate behavior in the future. This is hard work and requires a regulated emotional and cognitive state. Students are not able to engage in restorative practices when they are emotionally deregulated (e.g., overly scared, angry, sad, etc.). Engaging in a calming activity helps to regulate students so they can bring their full self to understanding the impact of their actions and making an appropriate commitment to making things right. The calming activity is only the first step in a comprehensive response plan.

- We should also note that children come to the office for a variety of reasons. They celebrate accomplishments with office staff, audition for speaking parts in morning assemblies, ask for help solving problems, etc. Some children have proactively scheduled breaks outside the classroom to help maintain a state of appropriate regulation. A student may have a schedule to play a brief game or perform some other fun, calming activity in the office. The child is still responsible for classroom learning and the long-term goal is to build stamina to stay in the typical classroom setting for the entire day.

How do we use restorative practices when bullying occurs?

- It is important to have a common definition of bullying. All hurtful actions are serious and must be addressed, but not all hurtful behaviors are bullying. Bullying is mean or hurtful behavior that keeps happening. It is unfair and one-sided. The Second Steps Bullying Prevention unit defines bullying by three primary characteristics:

- It is aggressive behavior that is usually repeated over time.

- It occurs in a relationship where there is an imbalance of power, and

- It intends to cause harm or distress and/or has a serious harmful or distressing impact on the target.

- We also take proactive measures to prevent bullying at all grade levels in primary school. Teachers and school counselors teach lessons from the Second Steps Bullying Prevention Unit. The lessons incorporate instruction, videos, songs and structured class discussion on recognizing, refusing and reporting bullying. There are also lessons on appropriate bystander power and cyberbullying.

- We teach children to report bullying immediately to an adult. We take reports of bullying very seriously and take action immediately to stop bullying behavior. We use the “Regulate, Relate, Reason” approach described above, with special emphasis on understanding the impact of actions and developing empathy with those hurt by bullying behavior. Sometimes we quickly get to the root or cause of the problem. Students understand the impact of their choices, take responsibility, make things right, and assure staff and other students the behavior will not continue. When all students involved report that they feel safe and ready to try a new plan, and the staff are confident children have skills to be safe, we monitor relationships while we ensure the problem is solved. We regularly check in with victims to make sure they feel safe and empowered to with age-appropriate response for refusing and reporting bullying in the future. If we lack confidence the problem has been resolved, we employ additional strategies as appropriate, such as additional instruction in small group settings, meetings with parents, additional supervision, check-in/check-out protocols, etc. Repeated problems on the school bus may result in an assigned seat or suspension from using transportation services. Repeated problems at recess may require a loss of recess while new skills are learned.

- Restorative practices may not always work in situations where there is an imbalance of power. Careful consideration will be given to not re-victimizing students in a bullying or imbalance of power situation.

Bibliography

Basch, C. (2010). Healthier students are better learners: A missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. Equity Matters Research Review, No. 6. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. Retrieved from https://healthyschoolscampaign.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/A-Missing-Link-in-School-Reforms-to-Close-the-Achievement-Gap.pdf (Page is currently unavailable.)

Blankstein, A., & Noguera, P. (2016). Excellence through equity: Five principles of courageous leadership to guide achievement for every student. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Boyes-Watson, C., & Pranis, K. (2015). Circle forward: Building a restorative school community. St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press

Boccanfuso, C., & Kuffeld, M. (2011). Multiple responses, promising results: Evidenced-based, nonpunitive alternatives to zero tolerance. (Publication #2011-09). Washington, DC: Child Trends. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Child_Trends-2011_03_01_RB_AltToZeroTolerance.pdf

Elias, M. (2016). Why restorative practices benefit all students. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/why-restorative-practices-benefit-all-students-maurice-elias

Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., Goodman, S., Mitchell, B., George, H.Swain-Bradway, J., ...Putnam, B. (n.d.). PBIS technical brief on systems to support teachers’ implementation of positive classroom behavior support. Retrieved from https://www.pbis.org/Common/Cms/files/pbisresources/PBIS%20Technical%20Brief%20on%20Systems%20to%20Support%20Teachers%20Implementation%20of%20Positive%20Classroom%20Behavior%20Support.pdf

Payton, J., Weissberg, R., Durlak, J., Dymnicki, A., Taylor, R., Schellinger, K., & Pachan, M. (2008). The positive impact of social and emotional learning for kindergarten through eighth-grade students: Findings from three scientific reviews. Chicago, IL: Collaboration for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL). Retrieved from https://www.casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/the-positive-impact-of-social-and-emotional-learning-for-kindergarten-to-eighth-grade-students-technical-report.pdf

Restorative Practices: Fostering Healthy Relationships & Promoting Positive Discipline in Schools (2014). Retrieved from https://advancementproject.org/resources/restorative-practices-fostering-healthy-relationships-promoting-positive-discipline-in-schools/

Stutzman, A., & Mullet, J. (2005). The little book of restorative discipline for schools: Teaching responsibility; creating caring climates. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

U.S. Department of Education (2014). Guiding principles: A resource guide for improving school climate and discipline. Washington, D.C.

Wachtel, T. (2016). Defining Restorative. International Institute of Restorative Practices. Retrieved from https://www.iirp.edu/restorative-practices/defining-restorative/